PaleoPeople PaleoPeople

Leif Tapanila

Idaho State University, Pocatello, ID, USA

— Interview conducted May, 2008

Leif Tapanila grew up in the Sudbury impact crater in Canada before heading out to the University of Waterloo for his biology degree. He returned to Sudbury for his Masters in geology, working with Paul Copper at Laurentian University. For his doctorate, Leif headed southwest to the University of Utah to work with Tony Ekdale and received the geology department's Outstanding Ph.D. Award for his work on erosional and symbiotic trace fossils. Afterwards, Leif joined the Department of Geosciences at Idaho State University as an Assistant Professor and he also serves as Curator of Geology at the Idaho Museum of Natural History. His current research includes studies on the environmental recovery following the Alamo meteor impact in Nevada, the ancient ecology at the margin of continental seaways preserved in southern Utah and West Africa, the fossil record of symbiotic associations, and the development of teaching software for paleontology and historical geology classes. |

|

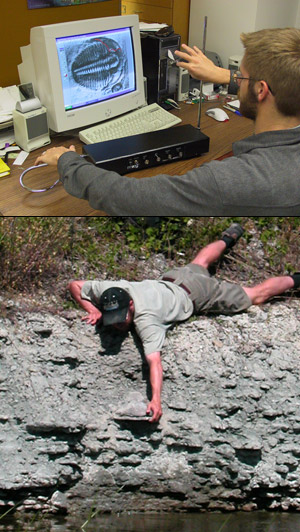

Top: Teaching fossil shapes with sound. An innovating teaching approach developed by Tony Ekdale at the University of Utah, students use a moog musical instrument to "play" the sound of a trilobite's cheek. Photo by Tony Ekdale. Bottom: Reaching for a 420 million year old sponge: these fossils in Sweden preserve close interactions among animal species. Photo by Jan Ove Ebbestad.

|

Q: Would you tell us how you got into science and into paleontology in particular?

A: As a kid I was certainly aware of dinosaurs

my brother was really into them, but I never would have predicted that I'd be a paleontologist when I grew up. My earliest ambition was to teach. Both of my parents are artists and teachers. I was good at math, but in grade 11 I had a bad math teacher, so I wasn't really enthusiastic about pursuing math. On the other hand, my 11th grade biology teacher was great! I ended up doing my undergraduate degree in biology. I loved natural history, so when I took an introductory geology class during my Bachelors, I realized that I could meld together biology and geology through paleontology. Doing a bit of research for my Bachelors degree with Paul Copper got me hooked! I decided I wanted to get a faculty position somewhere. That meant going on for my Masters and Doctorate.

Q: What research are you working on currently?

A: My research may seem a bit scattered

I am mainly an invertebrate paleontologist with an emphasis on trace fossils, but I also work with vertebrate material and spend a lot of field effort understanding the sedimentology of my areas. I'm working in West Africa, southern Utah, southern Nevada, and points in between. I usually have six to eight projects going at any one time. I work on one for a bit, then go and work on another. I may get frustrated with a lack of progress on a particular piece of research, so I move on to a different one

sort of like moving pawns forward on a chess board. I'm particularly interested in ecosystem change

the interaction of organisms with each other and with their environment. These interactions can alter the ecosystem through time. I have a big project in southern Nevada, working on a Devonian-age impact structure. I'm looking at how the marine system that was present at the time was affected by the impact and how the system recovered. It's a really good site. There are coral reefs that grew right on top of the impact structure, and it appears as though, ironically, the impact may have helped a new ecosystem develop: reefs growing where none did before. I am also collaborating with researchers that are pushing the frontiers of geology: southern Utah was one of the last areas of the country to be mapped. We are looking at Cretaceous rocks to see what organisms and environments were present in the region back when the center of America was covered by a seaway. A similar kind of seaway crossed through West Africa, and so these two projects share a lot in common. The best part of working in frontier lands is that nearly everything you find is new to science

so there's a big payoff for the hard work!

Walking in the footsteps of a dinosaur, Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Utah. Photo by Pat O'Connor.

|  |

Q: How would you describe a "typical" day for you?

A: My work really has "seasons" and a typical day is different in each season. For nine months of the year I am teaching classes and advising graduate students. I also do a bit of administrative work, and I'm a part-time curator for the Idaho Museum of Natural History. During the spring and fall I fit in research mainly writing grants and papers where I can between classes. The other three months is a combination of a little vacation and lots of field work. When I'm in southern Utah and southern Nevada it's pretty much solid fieldwork to get in as much time as possible on site. Lots of camping and hiking outside

you can't beat it!

Q: What would you say is the most exciting thing that has happened to you in your career as a paleontologist?

A: Traveling to exotic places

West Africa, for example. That's about as exotic as you dare to get

traveling in the desert for weeks at a time. Not only is the terrain exotic, but you face a number of physical challenges

the temperature is extremely hot, 110°F plus. But there is always the feeling that you are doing things that no one has done before. The possibility of "discovery"

that excites me. One of the really fun places I work is in southern Nevada, near the town of Rachel

and Area 51!

Q: Do you run into people wearing space costumes?

A: Oh, yes! And there's a little restaurant in town that plays on the whole alien theme.

|

Top: Gee, its hot. The Sahara Desert in Mali holds many ancient secrets that keep us coming back for more! Photo by Eric Roberts. Bottom: Teaching geology in the field is a fun part of my job. Sandstones near Price, Utah, show students how burrows are useful in identifying ancient environments. Photo by Steve Cox.

|

Q: You chose to go on for a Ph.D. when you decided you wanted a university faculty position. Are there any paleontology jobs for people without a doctorate?

A: You can do paleontology without any formal degree. Paleontologists often work with amateurs. You can volunteer with local museums. If you want to be a professional paleontologist, a Bachelor's degree is usually the minimum requirement. Some of our Idaho State students have gone into consulting. Oil pipelines are being built in Wyoming, Colorado, Utah and other places, and companies need someone qualified to determine whether there are any fossils in the path and evaluate their significance. This is a practical application of paleontology and a well-paying job. On the research side, one of the best expedition leaders that I know doesn't have a Ph.D. He does research, writes papers and manages dinosaur digs. Of course, if you want to teach at the college or university level you pretty much need a doctorate. So, I'd say that there are many opportunities at all levels for people to get involved.

Q: Why is the study of fossils important in today's world? Is paleontology really relevant?

A: The fossil record is a tangible link with our past, and in the ever-changing world we face today, the study of ancient life helps us interpret where we come from and advise where we are headed. As a branch of the earth sciences, paleontology continues to contribute significant information on the developing theories of plate tectonics, global climate change, and of course, the evolution of life. Beyond these technical aspects of Earth history, fossils make learning about science fun and accessible. From T. rex to the trilobite, fossils catch the imagination of adults and children alike. The simple joy of discovering fossils while out hiking can open our eyes to a rich history full of wonder

and with the help of the paleontologist we can appreciate our modern world within the broader context of Earth history.

Q: What advice would you give to young people considering a career in paleontology?

A: Always follow whatever your passion is. I learned this from my parents. If paleontology is what you're passionate about, go into it full tilt. There's a lot of competition in paleontology, so you need to stand out. This usually means showing passion. Love what you do. Of course, you need to keep up with the math and sciences: biology and geology are the foundation for paleontology. Get involved with your local university or museum and start working with paleontologists, as a volunteer or field assistant. But it all starts with passion. Don't hold back! |